by Lucy Euler

Art by Vivian Huang

Issue: Kalopsia (Spring 2017)

The girl with cancer dies at the end.

She was important to me, sure. Arguably, she wasn’t anything to me, really, because she was so many things at once that half the things cancelled out the other things and she was nothing more than a human oxymoron in my life. Her mother, (who, to put it nicely, was psychotic and deceitful and idiotic and cowardly and the worst kind of self-absorbed) dated my widowed father for less than two months last year and then convinced him to marry her, only to disappear the day after their wedding and leave behind a jaded seventeen-year-old opposed to happiness and eye contact. She became my sister—stepsister—and my roommate, and the closest thing I had to a friend, but most of the time she was but a stranger roughing it in a well-crafted blanket fort between the foot of her bed and the wall, where there had once been a recycling bin.

She moved into my room on a Sunday and didn’t talk to me for seven weeks. She sat, brewing, in her fort every day from four in the morning to later than late, safe from the beauty of the world and the gloom of the house, and wrote, filling pages and pages of loose-leaf binder paper each day. I once asked to read a page or two and she glared at me through a gap between the white blanket walls and threw at me a small red pencil sharpener. It hit me on the side of my head and it hurt and I didn’t say anything, but when she resumed her writing I stuck it behind my dresser so she’d have to ask me where it was.

She didn’t. There were no questions asked—she didn’t care to speak to me. And there was no longer that curdling splintery sound of metal biting into graphite every five minutes. There was just silence, filling my head with a bitter empty space. The hollowness grew within me, from the inside out, and pushed a lump into the back of my throat. I thought she would break when she ran out of usable pencils, but when she did she sloppily searched the house and found a dusty drawer-ful in the desk downstairs. I cried that night, silently and on the edge of restless sleep. I was starting to forget what feelings sounded like, and I didn’t want to remember.

The next morning, however, I’d forgotten that I didn’t want to remember, and lay in bed evaluating my ever-hardening attitude towards her and her ever-hardening attitude towards me and said, quite plainly to the five-a.m. dark, “Aren’t you dying?”

It wasn’t the first time I had tried to make conversation with her, but it was the first time I had asked something so forward, so blunt, so accusatory. I closed my eyes, shook hands with silence, and knew to not expect a word out of the girl who wouldn’t answer when I asked her about the violent summer storm thrashing outside our window.

“Aren’t you?”

Her voice had me picturing the lingering coals and embers of a watered-down fire: it was seamlessly glowing but crepitating at the same time, and she sounded almost as though she had spent thirty years smoking. But I was dumbfounded. She had said a whole two words to me and I was suddenly speechless.

Minutes passed before I spoke. “But you know when you’ll die, don’t you?” I was suddenly conscious of each word that left my mouth.

“The last doctor said around two to three months, but that was two months ago. So any time between now and the start of school, I suppose,” she said, with little sentiment towards time.

“But that was without treatment.”

“Why would I want to live any longer?” She cleared her throat and choked a little in doing so. “All I see is pain. All I hear is pain.”

I supposed she didn’t want to speak of the doctors she’d been refusing to see, the meds she’d been refusing to take, the life she’d been refusing to enjoy. So I asked, “What does pain sound like?”

“A door slamming again and again, indefinitely,” she said without pause for thought. “And it’s not just the pulse that runs through your ears; it’s all the emotions that go with being shut out, or shut in.”

“Is that what you write about?”

She didn’t answer, but I lay staring at the ceiling for hours waiting for a response.

And in those hours, she didn’t move. The sliver of daylight the rainclouds offered in the later morning revealed that she was not in her fort, but lying flat on the floor between our beds and crying, not unlike how I’d cried the night before.

I rose from my bed and stood over her. “Look at me.”

She made no effort to, but I stared into her eyes as she stared into her pain and I wondered if I would be able to tell if she died right then, in that position and with tears still rolling into her ears. I shuddered at the thought of witnessing her death, even if it was as uneventful as a drift into a state identical to how she looked right before her last breath. I nudged her with my foot and a scream-like noise seeped out of her closed mouth.

She then opened her mouth, but the words came out slurred. “Everything hurts.”

“Do you want ibuprofen?” She said no. “Breakfast?” No. I left and came back with a glass of water. “Are you thirsty?” She only shrugged. She sat up and her eyes spilled onto her shirt. I sat crisscrossed in front of her and she looked directly at me, but I got the feeling she couldn’t see me through the tears and weak lighting. I urged her to help herself but her mind was elsewhere: she asked if, after she died, I intended to read everything she’d written. “Yes, yes I do.” She smiled a dazed smile at the floor and said she wanted me to.

Suddenly but slowly, she rose and with most of her strength slid the window all the way open. The storm breathed into the room and nearly threw her back down. The rain reached in diagonally and bled from the windowsill down the wall, stopping at the already warped baseboard.

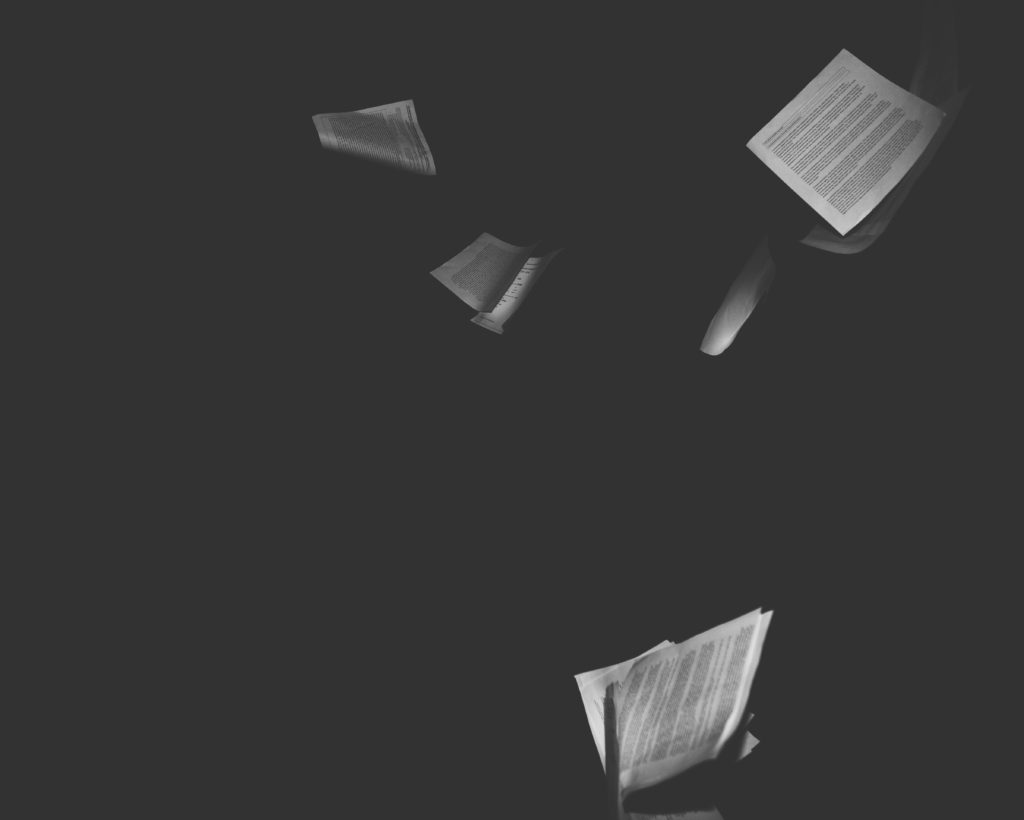

And she took everything she had written in one towering armful and threw it all to the wind. There was a fluttering and a ripping as paper separated from paper and flew in every direction, plastering the yard and the agitated sky with her work.

“What did you do that for?” I exclaimed, rushing to close the window.

She shook her head and looked away and told me to salvage whatever I could. I grabbed her by the shoulders and would’ve shaken speech out of her if she hadn’t felt so frail and lifeless in my grasp. I wouldn’t have let go until she told me what she had been thinking: what compelled her to give away a summer’s worth of words; why she allowed herself to fall out of character just long enough to make me think she cared about me, only to take it all back by giving away all she had promised me.

But I left when she told me to leave, and I heard the door slam shut as I made my way down the stairs. In the hallway I passed my father—our father—who, forever in the thick of depression, barely requited a hello. He disappeared into the den and pulled the folding doors together behind him. The TV got louder. He didn’t laugh with the laugh track.

The wind pushed the door into me as I stepped out onto the porch. The yard was made up like an Easter egg hunt with soggy paper instead of plastic eggs: they were tucked away in the trees, lodged in bushes, and there was a great mess of them along the fence. I went for a nearer one that was flattened to the colorless patio.

If I don’t talk to you, I can’t get attached to you. If I can’t get attached to you, I can’t confide in you. If I can’t confide in you, I can’t tell you that I love you. If I can’t tell you that I love you, I’ll find some other way to let you know. If I find some other way to let you know, it’ll be too late.

It was the same five sentences repeated over and over to fill the front and back of the page. It was the same five sentences repeated over and over on every single page, every piece of paper within my reach. I hurriedly collected as many as I could, reading through each one as if the same words could tell me anything more. But I found no other way to interpret “too late.”

I ran inside and flew up the stairs. My damp shoes slipped out from under me on the last step and I fell, chin-first, onto the hardwood floor at the top. The pain pushed more tears out of my eyes but I picked myself up and continued towards the bedroom. A light from inside spilled out from under the door, cutting into the darkness of the hallway. I had expected the door to be locked but it opened easily and revealed a post-hurricane wreck. Sheets and mattresses were overturned. Drawers were out of my dresser with their contents spread across the floor. The dresser itself was moved crookedly away from the wall.

She had found the sharpener, and had left it on my bed without the blade.

I looked around the room for her and saw only the outline of a body loosely covered in the blankets of a fallen fort. And the blankets grew redder.

The girl with cancer died at the end.