To Feel Within the Void

Kaylia Mai | Art by Christy Yu

When she wakes, her first thought is that the ceiling is blindingly white. Jess blinks confusedly at the ceiling. She cannot feel her arms. The IV stand beside her splits in two and merges again. A faint impression tells her she already knew all this.

What? I don’t understand.

Disconnection. Jess floats in the void; towed around by the medication flooding her system. The door opens and a doctor comes in. Did the door close? And then she thinks, the lights are really bright. He speaks words like accident and lucky and prosthetics, but she hardly processes because she looks down and where-is-it-where-did-it-go-it’s-supposed-to-be-there! The sheets were flat where her left leg was supposed to be. Jess stares in a trance of horrified wonder. Maybe her leg was folded under the other one?

Words flow over her, and she thinks they sound nice. They’re so fluid, and normal, and it’s so hard to believe because normal is impossible. That’s something that happens to other people, maybe, but not her. Not anymore. Not ever again. She giggles to herself, a little hysterically. Medication is nice, she thinks, everything is all floaty and muted and nice.

At some point she must have moved, or been moved. She must have signed something, or spoken to someone, or been lifted into a wheelchair, because she’s somewhere else now. She thinks, oh, I know here, and she does. It is the apartment she and her boyfriend Timmy share. They got it together a long time ago, before this. Jess can hardly recall. None of it matters. The walls of the apartment are white. She always imagined the void would be black, now she knows it is not.

Timmy wants to know if she wants a glass of water. Jess wants to know why the void is as white as a hospital room. Their puppy, Sugar, wants a walk.

“Sorry boy, I’ll pay one of the neighbor’s kids to walk you, but you’ll have to wait until they get out of school.” Jess mutters, patting his head.

Before the Incident, and it seems like a lifetime ago now, Jess loved running. She loved the feel of wind whipping through her hair, the fresh scent of pine along the trail, and the burn of her legs as her feet pounded the ground. Jess had played tennis and gone to practices every Saturday morning. Jess had run along the mountain trail by her house every afternoon, and walked Sugar in the evening. Jess did all of those things, but she was no longer her.

Normal is such a strange thing. Everyone else finds it so easily, but not her. She cannot find what does not exist. Standing is an achievement. Walking is an impossible feat. Running? Inconceivable.

When the prosthetic arrives a month later Jess is again sitting on that couch. It is one of the only places left that she can be, and watching terrible television is one of the only things left that she can properly do.

Timmy claps his hands. He tears open the packaging, and exclaims excitedly over the metal monstrosity inside. Jess… watches. It has been a long month, and although she has hardly done anything, fatigue plagues her. Now she cannot find it within herself to be excited at all. It is only for Timmy’s sake that she bothers to try it at all.

“…and you’ll be right back up! Jess! Jess, c’mon you have got to be so hyped for this, try it on!”

The leg is clunky and awkward. She hates it. Leaning heavily on her one good leg, it feels like a spectacle as Timmy and Sugar watch her trip over and over. In life, she had run a mile without breaking a step. In life, she had leapt out of bed every morning without sparing a thought for it. She does not know what life is anymore. It certainly cannot be this painful, writhing, hot thing inside when they see her stumble, because this hurts.

“Well maybe it takes a bit of practice to get started. Of course practice will make it better. Let’s walk around the counter a couple more times alright?”

“I don’t want to walk around the counter again! I hate doing this! Why can’t you just leave me alone?!”

“Let’s just try one more-”

“No! I’m not doing this anymore. It’s useless. I won’t play tennis ever again. I won’t go running. I won’t walk Sugar. I’m done.”

Her shoulders slump. The strain of helplessness, of spending weeks cooped in a single room burst forth as rage, but Timmy falters and it fizzles just as quickly. The cloud of numbness settles back on her shoulders, but now layered with a wave of shame. “…I’ll try again tomorrow.” she mutters and collapses back on her couch. She stares at the wall. It’s blinding white stares back into her.

Sugar barks at her and runs around and around her. Even the puppy can run.

Jess waits for that irritating optimism that Timmy always throws forth, for him to pull her up for the hundredth time, but he just nods. His face is unreadable, but he just keeps nodding and walks away.

“I’m going to go do the laundry and run some more errands, goodnight Jess.” he says, and he is gone.

Guilt hurts. It pierces the numbness and drags her through the fatigue that had oppressed her for weeks. For the first time Jess considers, too late, how the Incident affected Timmy. Then she turns the thought over and finds it is not the Incident affecting him, but her.

The white wall stares as always, and she is so tired of it. She just wants it to stop. She wants that soul-sucking pull to stop. She can not do this anymore. And she storms to the garage, not even noticing the clunky awkwardness of the leg, and grabs a bucket of paint. She blunders back to that room and that taunting wall. Her hand plunges into a mixture of multicolored paints, grabbing them up in a fist, and she flings it across the wall. She scrapes at it with nails and the flat of her palm until the whole wall is a brown mangled mess and she thinks viciously, now you are like me too.

But between the browns, small streaks of bright, unmixed colors peak out at her. Suddenly, she fully processes that she is standing, that she had walked the ten paces to the garage and back, that she had hardly even noticed while doing it. A thought occurs to her, one she had had many times, but this time there is no more excuse.

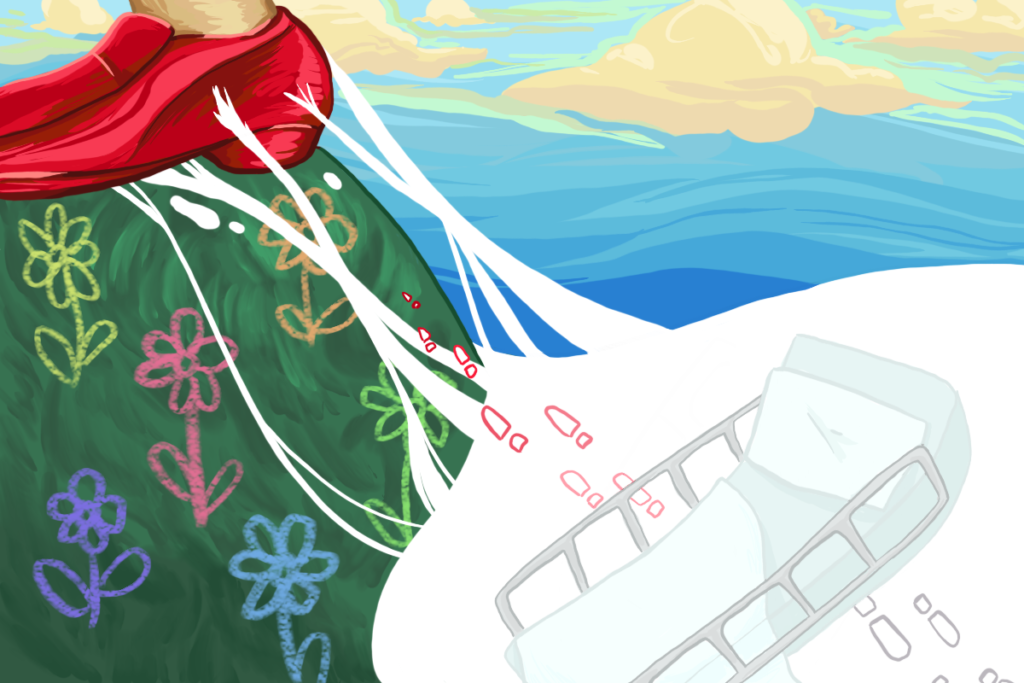

She runs. Jess sprints, no, she stumbles and wobbles, down the mountain trail. A leg and a hunk of metal struggle to support her. It is not fast by any means, or even comparable to walking speed, and yet this is not humiliating. There is a bursting warmth, a forgotten piece of life reignited, and she sets her jaw against the frustration at her body. Foot moves over metal hunk, which moves over foot.

Her chest burns and her body aches, and she’s tired, but not the same kind of tired. This new tiredness is so large, it encompasses so much inside her, that there’s no more space for that old, bone-deep exhaustion.

Standing at the top of a small hill, the ten feet she managed to travel behind her and the mountain trail before her. There is no white void here, out amongst the crisp green leaves and brown earth. Jess has re-learned pride, but there still remains a gap of wanting more and reclaiming herself. Her old normal is lost–forever–and there’s no changing that. But here this is something else. It’s not normal, not quite, but maybe someday it can be. Her new self is only layered on her old life, a brown with multicolored highlights, and she walks away from the pull of the void.