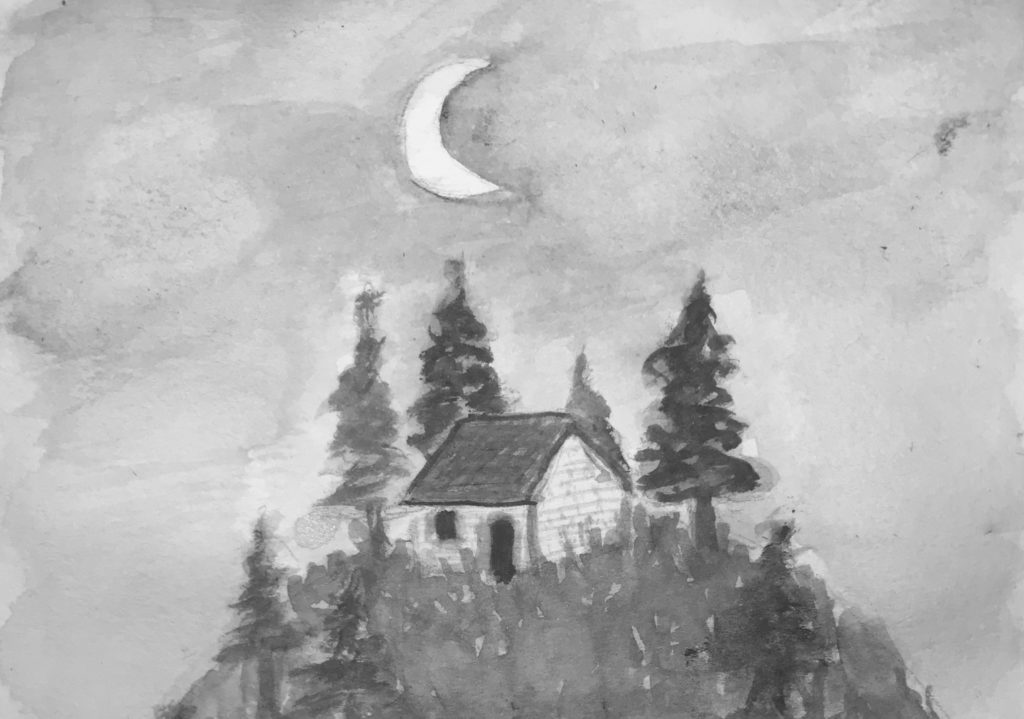

Dixie On The Hill

Alisha Bose | Art by Angela Sun

It was only when the trees were black shadows and the stars hadn’t come out yet that she wanted to play. During the day, she’d be locked up in the little thatched cottage on the top of the hill, the wall of barely blooming honeysuckle separating her from the rest of the world. No one else’s plants would grow—tomatoes, flowers, even cacti would all shrivel up before they had grown to be bigger than a ping pong ball. If one tried to salvage it, it would fall apart. The Island bloomed for nobody, except her.

The other kids wouldn’t speak to her either. The time to themselves was limited, and one would hardly waste it mooning over a mystery. When school started, the time to themselves became even more scarce. On an island where danger lurked in one’s very own house, curiosity was discouraged. Dixie, however, couldn’t shake off his interest in the little girl in that lonesome house.

Their cottage was far off on the hill. It was hidden in a little nook between the trees and well apart from the rest of the village. Her windows hadn’t been painted over. Dixie’s, and everyone else’s were completely black, to protect themselves from the Island, but one could see everything inside the house.

When he felt brave, he would climb a tree near the house and try to look through the window. She was never there, but an easel and a blank canvas was, against an eerily white wall. In a few weeks, images started to form on the canvas, strange slashes of color that didn’t seem to work together well; yellows with dull greens, splashed over with oranges. The finished product was a bizarre myriad of shapes that formed an ugly portrait of a young boy. The next canvas was simple—five letters of violent magenta—hello.

For a while after that, he didn’t come back. He stayed with the other kids, played hopscotch far from the woods, and never lingered too much at the edge when the sun started to set. It was one thing to treat her like an invisible artist, but after sunset, she became more sinister; less human and someone Dixie didn’t want to mess with.

Children were never supposed to be outside after dark. Adults could stay, if absolutely necessary, but had to head back immediately if they couldn’t see the Moon at any point. The Island was kind when the Sun watched over, but the Moon was too weak to protect them when the Clouds took over.

He tried to stay true to his promise, but the Island listened to no one. It had been a working day, and there’d been a more difficult batch of tourists than usual. They’d fussed, tried to take pictures of the Island folk, gotten into their houses, and had overall been a nuisance. Despite the last ferry back being at four, they’d somehow stayed till five. The Mainland folks were oblivious of the dangers of the Island, and it was reflected in their stupid grins and foolish faces.

But because of the hold-up, the dogs hadn’t been taken out all day. When Bear started whining, Dixie knew they needed to go out.

“Let them go in a cup,” Maman said brusquely. Night scared everyone except Maman, who would simply tuck him in with a sad smile on her face. “It’s curfew, Dixie. And you need to take your medicine.”

He nodded, but Dixie never liked the way the house smelled after using the cup. The smell would waft through for days after. A sliver of the Sun was still out, and the dogs were old enough that no one would miss them if they were Taken, so Dixie slipped out of bed.

It was through that tiny crack in the door that he saw the light, shining all the way from the hill. If he squinted, he could just make out the tiny lantern. It moved quickly around the house, held up by some sort of invisible ghost.

The dogs weren’t done yet, so he looked on with reckless abandon, straining to see the owner of the mysterious light. He watched as they made their way down the hill, using a path he didn’t even know existed. For a moment, they stopped at the crest of the hill, as if waiting for someone.

It was too dark and silent. With a start, Dixie realized that the Moon had been taken by the Clouds.

“Get back in!” he hissed at the dogs, who whimpered. Dixie almost closed the door on their tails, but he couldn’t bring himself to care.

Right before the light had gone out, where the hard glint of the soulless stars was the only thing illuminating the tips of the trees, he could have sworn that he had seen something shining; a glint of lonesome blonde hair.

He leaned against the door, trembling and trying not to wake Maman. There was no other plausible explanation—she must have come out. She had come out in the night, when there was no Moon.

So, the next day, he hiked up the long way to the house. It was just to see if she was okay, he reminded himself. If she had been Taken, it was customary to put a red circle on their door. He was there to check their door, nothing else.

But once he’d reached the top, he couldn’t resist going to his old spot in the pine tree in the back of the house. To see if she was okay. The door didn’t have a circle on it, but perhaps it was because the house was so odd. She wasn’t alone, he was certain of that. No child could stay alone on the Island and live to see the days pass.

He carefully made his way up the branches, climbing a little higher than her window so he could have a better view. He parted the leaves with one hand, grasped onto the branch with the other, looked and—

There she was.

There was no doubt about it. Her hair was the same blonde he had seen that night, long and wispy, nearly up to her thighs. She was in an extremely loose, white gown, and her eyes were startlingly pale—like large, gold plates looking straight into one’s soul.

They watched each other for a few seconds, green eyes on gold each challenging the other to make the first move.

As so it happened, it was Dixie who lost.

His foot slipped from its hold below, and he was forced to break eye contact and grab onto another branch. She smiled a little, emboldening Dixie.

“I’m Dixie,” he said. The wind rustled the dead leaves on the ground, harshly raking them against each other.

She paused, then moved closer to the windowsill. “Clover.”

Her voice was dry and raspy, extremely unlike any other little girl Dixie had ever heard. It was low, too, completely different from the high-pitched sounds the schoolgirls usually made. Still, he wanted to hear more.

“What’re you doing up here all alone?”

She kept staring at him, almost like she was scared he would disappear if she blinked. “I’m not alone. I have Eve.”

“Is Eve your Maman?” Dixie asked curiously. Every child had a Maman in some shape and form, someone who tried to protect them from the Night. Sometimes they failed. Sometimes they didn’t.

“I don’t have a mama,” Clover whispered. “Eve is just Eve.” She stuck both hands out of the window, towards Dixie.

“Why don’t you come to school with us?” Dixie moved closer. He could almost touch her veiny, white hands with his own if he leaned down.

“I ‘spect Eve won’t let me. I never talk to no one.”

Dixie frowned as he slid forward on the branch. “That’s not right. It’s anyone, not no one. You’d know that if you came to school with us. We have an empty seat, right next to me.”

Clover smiled. “That’d be nice, Dixie. I hate being alone with my books and Eve. She don’t talk to me either. No one does.”

“No one?”

“No one.”

Dixie precariously hopped onto a lower branch, scratching his uncovered shin. “Well, you can sing, Clover. That’s what I do when I’m sad.”

“Sing?”

Dixie landed on the branch right outside her window and took her hand. He’d never seen anyone with such frail hands. “Sure, we can sing anything we want to.”

He tipped his hand back and sang the first thing that came to his mind. “Little silver bells, ringing in their shells, ten o’clock, eleven o’clock, and here flies the hawk!”

“I like it,” Clover said. “I like the rhyme.”

“We learned it just yesterday,” Dixie informed her importantly. “It’s our very newest song. Do you do anything else here?”

She smiles thinly. “I like drawing. Did you see mine drawing? I knew you was coming around, so I drew a drawing.”

“The drawing?” Dixie thought back to the ugly portrait. “Was that for me?”

Clover nodded eagerly. “Did you like it?”

Dixie shrugged. The Sun was beginning to fall back. “I should probably be going, Clover.”

She looked visibly disappointed. “Oh, but can’t you come again tomorrow?”

Dixie considered that. He never had much to do after school, and this little mystery at the top of the hill was more interesting than any of his books. Still, the little cottage was so far apart from everyone else, and it took a long time to get to it.

Clover seemed to sense his hesitation. “There’s a shortcut!” Clover notified him in excitement. “Eve uses it. I seen her going down and I use it when it’s dark. See right there? It’s right there.”

Dixie twisted, and through the foliage he could just make out the beginnings of a small, barely used path. It would make his journeys up to the hill much easier and faster.

He mulled it over for a second, and looking into her hopeful, golden eyes, he conceded. “Okay,” Dixie said. “I’ll come back tomorrow.”

And so he did. It became a daily tradition, the hike up to the hill and climbing the tree. Clover took out new canvases for them to paint on, and Dixie taught her the songs that they learned during school. He never saw Eve, but Clover would often share the goodies that Eve had gotten her with him.

Maman never brought him candy or Jell-O, but Eve did. One day, he even took the dogs up the hill, and let Clover wave at them. She had never seen a dog before, but had said that she quite liked the look of their floppy ears. Their little rendezvous continued for quite a while—until one day, Clover wasn’t in her room when he arrived.

“Clover?” he called. “Clover, where are you? We learned a new song today in class. It’s called Rosy Rosy Was A Little Nosy. It’s really funny. I wanna draw her. The teacher said Rosy has the reddest cheeks in the whole wide world! Redder than mine!”

He jumped the short distance from the tree to her room and stared. Her paintings had all been stacked up, and the room was even more bare than normal.

“Clover, we just painted that!” he cried, looking at the canvas with a sloppily painted house on it. “It’s not dry yet!” He moved it, wincing a little when the paint smeared, ruining it.

“Dixie!” a faint voice called.

“Clover?” he glanced around, then out of the window. “Clover, is that you?” He poked his head out of the window, and tried his best to see through the thick foliage. But the fruits had started growing and he couldn’t even see the shortcut that he had taken. He could’ve sworn that he had heard the voice from there, though, so he hastily put his foot on the windowsill.

In his haste, he forgot to grab the branch. His foot slipped, his hand just grazed the leaves—and then all was black.

▢

“Dixie!? Dixie, what happened? Can you hear me?”

“Don’t worry, he just slipped a little. He looks completely fine.”

Dixie blinks once, twice, then opened his eyes fully. He is lying on Clover’s bed, looking up at the dirty ceiling.

“Don’t scare me like that!” a calloused hand takes his roughly. “I’ve been looking for you for ages!”

Dixie turns to face her. “Maman?”

“He calls you Maman?” Eve asks.

Maman sighs. “Yeah, he was so young and overwhelmed on the first night… I let him do it. He’s so alone already.” She glances around at the room, her eyes lingering on the bright red canvases precariously set on the easel.

Eve threw Clover’s pillows into a basket marked For Laundry. “What’s he in for?”

Maman brushes a curly strand of hair behind Dixie’s ear. “It’s almost time for another round of chemo,” she responds as a way of answering. “You feeling up to it, bud?”

Eve shakes her head. “Heartbreaking. What was it this time? Deadbeat dad?”

“That, and the mother. Barely lasted these few years with him before they were put in jail and Dixie was, well, put in here.”

“Shame,” Eve clicks her tongue. “Some people should just not be allowed to be parents.”

Maman nodded her agreement, then turned her focus to Dixie again. She grazed his head carefully, pressing on the bump slightly. “Dixie, c’mon.”

“I don’t wanna go,” Dixie says stubbornly. “Where’s Clover? I thought I heard her, but now I don’t know where she is.”

The two nurses exchange a wary glance.

“How do you know Clover?” Maman interjects. “Have you been sneaking out during playtime?”

“Yeah. I taught her how to sing and she showed me how to paint. I took Bear too see her and—”

“—you took a therapy dog here!?” Eve asked.

“—and she said hi to him and I showed her some of my lessons because she didn’t know them and the Island was kind to her but—”

Eve puts up a hand to stop him. “The Island?”

“He has a very vivid imagination. I think this whole vision thing he has going is a coping mechanism. I’ve tried taking him to see a therapist, but… you know the kids. Bear works best for them, not an actual human,” Maman murmurs to Eve.

“Maman!” Dixie shouts, trying to get her attention back. “I came in here tonight and she wasn’t here! Maman, what happened to Clover? Why isn’t she here anymore? Do you think the Island took her!? Maybe—” he doubles over on the bed, coughing. Maman rushes to him.

“Dixie, we really need to get you back.”

“No! Where’d she go?” Dixie hacks out another cough. “Where is Clover?”

Maman exchanges yet another glance with Eve. With a sigh, she sits down next to Dixie. The bed creaks in protest as she shifts her weight.

“Dixie,” she begins very softly. “Clover… has moved away. She moved to another Island. She didn’t want to tell you because, well, because she didn’t want you to be sad. But she’s happy and safe.”

“Really?” Dixie perks up. “What’s this Island like?”

Maman puts a hand around him. “It’s–it’s really pretty. Her own Maman is there, too. And she can paint and sing all the time if she wants to.”

“No school?”

Maman’s smile doesn’t reach her eyes. “No school.”

“And can I write to her? All the time?”

“Sure, Dixie. Of course you can.”

“And you’ll send it to her? With a stamp and everything?”

“Yes, Dixie.”

Dixie flung himself against Maman and hugged her. “Thank you, Maman!”

She regards him sadly for a second before extending her hand. Dixie takes it. “Let’s go, Dixie.”

She leads him out the door and down the hallway. And as the door swings shut, a sign with a red circle flutters down to the ground, the words printed sad and haunting.

Vacant.