Attachments

Sophie Guan | Art by Joy Song

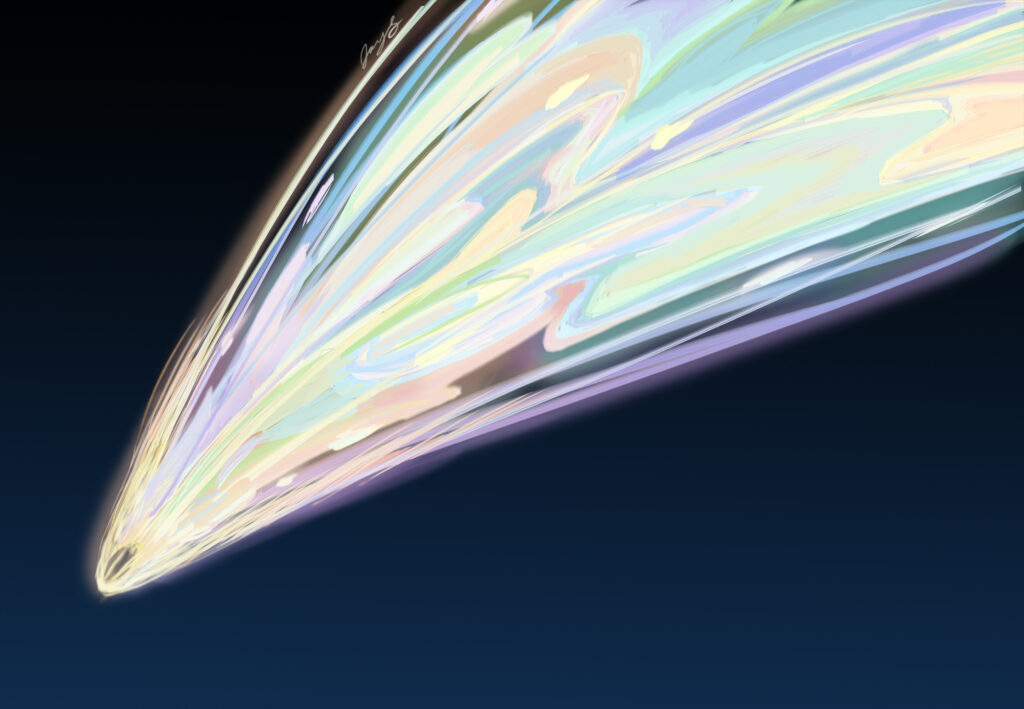

The streak of light tumbled from the burning heaven, slashed across the bright blue sky, and landed, quietly, atop the pile of melting summer snow. When the purity had completely submerged into the cobblestones mid-morning, the mailman came across a little, glowing pebble the color of the morning sky.

With a gloved hand, the mailman plucked the pebble from the ground and dropped it into a clear glass jar where it sat, after a few bounces and a soft cling, among the other pebbles that lay beneath it.

The light pulsing from the small pebble set it apart from the dark, black stones beneath, whose fervent glow was lost to the thieving time. Hours ago, they’d all been burning with brilliant life upon their arrival from the sky but now, they lay quietly on the bottom, their flimsy attachment to life having melted away like snow.

The mailman smiled, a finger gently tipping the jar the other way. The small pebble slid over with another bright sound, which reverberated over the shuddering exhaustion of the car engine as he slowed to a stop.

Outside the little white house, a middle-aged woman came to greet him. “Good morning, Mr. Lecter.” She wiped her hands on her white shirt and smiled warmly.

There were quite a few mails and parcels for her and he handed them to her in a small box. “Should I come back later for Maison?” he said after her sunspot-covered hands had a firm hold on the cardboard.

“Oh, Maison will be right out,” the woman said. “See, there she is.”

The girl wearing the color of evening primrose was seen sprinting out of the gray house, her black shoes sending little pebbles and sand tumbling in her wake. However, she cared neither for her appearance nor her disturbance, only that she was running as fast and as far as she could away from the house.

“Good morning, Cole,” she said, a little out of breath, and hopped onto the truck in three quick steps. “Goodbye, Headmistress.”

“I’ll see you in the evening, Maison,” the woman replied and nodded once to the mailman. “Please, Mr. Lecter, make sure she doesn’t interfere with your job.”

Cole smiled but didn’t respond. Behind him, Maison had already climbed into the back and taken a seat in a little blue bean bag reserved for her. They were a few streets well away from the house before Maison peeked her little head to the front. At almost seven years old, she had already lost to heavens the innocence that used to adorn her bright smiles. Its remnants lay only in the light sparkles in her eyes as she turned her face skyward.

To her, it’d been almost four months since her little brother Taury became a star. At least, that was what all the adults had been telling her. All adults but Cole, who neither agreed nor disagreed, but instead drove her silently, gently, and impassively around the cities and towns in her search for Taury’s star.

“Cole?”

“Hmm?”

“Do you think…Taury went to the sun? To the garden of souls?” she asked in a small voice. “Do you think he got tired of being a star and staying by himself?”

Cole merely shook his head. A little tinkling from the glass jar could be heard when he stopped before the red light.

“But it’s been months,” Maison said softly, a small hand worrying a ripped seam in the beanbag. “And I still haven’t found Taury’s star. Do you think Taury got tired of waiting for me to find him?”

Cole shook his head again and patted her hand. The soft glove between his hand and hers stole the comfort of the contact and left behind a faint coldness on Maison’s hand.

The sky was brilliantly blue today and not a trace of white hindered their view of the heavens. Above them, the garden of souls shone down upon them with reprimands. It chided her search, the glares clashing with the sparkles in her eyes, but Maison stayed because she knew Taury would only shine during the day, for his fear of darkness and nightfall would persist even as a star. The stars who chose to shine at night were those defeated by the sun and Taury was far more afraid of the dark than he was of defeat.

Cole got out of the car to deliver a few parcels. When he came back, she was still staring up at the sky as if in a trance. However, there was no reverie in her eyes, only a hardness that was reflected as well in the clench of her jaw and the reddening of her eyes and nose. Her little shoulders shuddered despite the warm, summer wind, so Cole asked if she wanted to stand under the sun for a little while. She shook her head.

They drove around the streets till twilight. On the horizon, the sun had set the sky on fire until it was charred. Tiny sparks of defeated flame flickered in and out and soon filled the sky. Cole returned the little girl to the house where the Headmistress was already waiting. Then, he went down the rivers by foot, carrying the little glass jar with him. Each step sent the pebble tinkling against the glass, a sound that was foreign to Cole who was used to the dull thuds of the heavy stones beneath it. The light was still there, illuminating the jar.

A woman waited for him by the riverbed, her feet drawing circles in the lucid stream illuminated by the moon. Cole emptied the stones from the jar into his palm and gave all but the pebble to her after consideration. It was a silent ceremony as she dropped the stones into the river. They clattered in protest and rolled over each other as if in some last regretful defiance before the stream engulfed them. It wasn’t long before faint white wisps drifted out of the stones, out of the water, and into the sky, heavenward.

“Give the pebble to me,” she said quietly as neither budged. “The river will cleanse the rock and return the escaped soul to heaven.”

He didn’t speak, so she spoke again, “the little boy has lived his chance. Even if he did escape heaven and landed on here, he cannot live a second time.” But perhaps out of mockery of her statement or a simple demonstration of the souls’ attachment to life, a star above them broke from heaven and tore across the sky. Cole watched it go and placed the glowing pebble back into the jar again.

“Cole,” she said firmly. “That pebble is not yours.”

He replied, “It’d be a waste to wash out the light.” Then he turned around and left her by the river to entertain herself with the dull river rocks.

Cole picked up the little girl in the morning as he always did the next day. She was quick to notice the lightness of the jar. “Where did the other rocks go?” Maison asked as she cradled the jar curiously.

“They went home,” he said.

“Oh, but what about this one?” she asked, holding it before her eyes. “Does it not want to go home?”

Cole looked at her strangely. “Why wouldn’t it?”

In the jar, the light was fastly fading from the pebble even as he spoke.