Ghost Parade

Danie Wan | Art by Anton Zhou

I remember feeling strangely detached — my fellow coworkers reveled and laughed around me, caught in the fervor of the afterparty. The night was still young, as it is in London and other large cities; though it was past midnight, they showed no signs of stopping, and neither did anyone else enjoying themselves in that small pub.

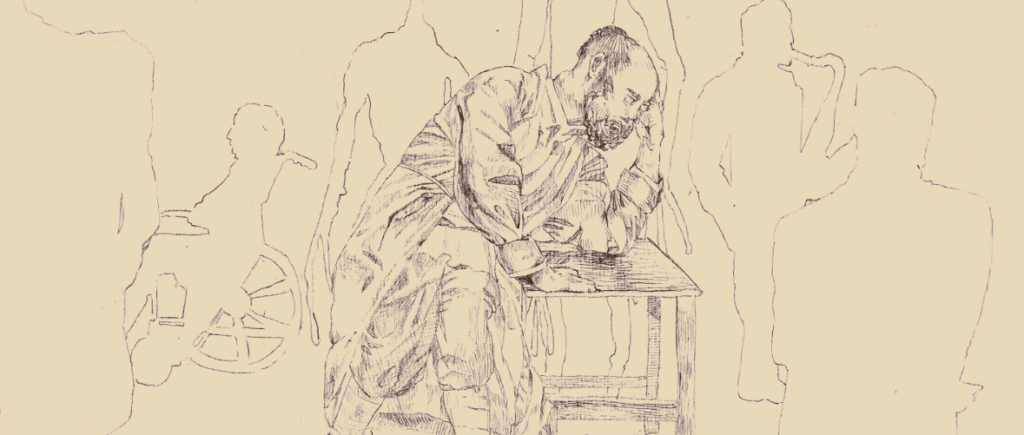

But I? I was far from engaged in the cheer and fun surrounding me. I was fresh out of university and had been shipped (with several others), by the small Chicago startup I joined on a whim, out to London to establish relationships in the area. If anything, my heart was not in this business, nor this party. My coworkers and their new potential business partners had taken to each other almost immediately, and they were having a great time; I sat there, a cold glass of beer in my hand, laughing and nodding superficially as those with thick accents, native to the London pubs, bantered and exchanged stories and jokes with others from the United States like myself. I was amongst them, yet I was listening from a great distance.

I was so lost in thought that I hardly noticed the buzz of my phone. Glad for an excuse to leave, I picked up the call without even glancing at the number, and quickly bid my companions farewell before stepping out into the cold night. The call was insignificant, nothing but a robot from some shady company, and I soon hung up. Hailing a cab, I quickly reached my small apartment, and threw myself onto my bed.

As I lay there, I could feel a wave of discomfort and discontent well up in me. It had only been a few months since I arrived in London, but my coworkers, a young, fresh crop of employees even newer than I, had already accomplished far more than I had, reaching out to companies, establishing friendships and relations with useful people. I had done little to nothing in comparison, clumsily lumbering my way through every interview and putting off replying to emails as long as I could without it getting awkward, and the feeling of inadequacy was getting to me. Emotions and thoughts washed over me, feelings which had now grown familiar — disappointment, uncertainty, anxiety, and an odd feeling of languor.

What are you doing with your life? The question spun around my head repeatedly, growing louder and louder until it consumed my thoughts.

Unable to bear the pain much longer, I sprung up once again, and stepped out for a walk.

It was approaching spring, and the snow had begun melting away — the remaining patches of white glowed under the streetlamps, while light sheets of rain draped over the streets of London. The sharp glare of traffic lights flickered through the raindrops, diffused red and green and yellow against a foreboding backdrop of dark shapes, just barely visible in the weather. Headlights flashed through the rain, illuminating the cracked stone curbs as tires

splashed water over them onto the sidewalks. It was wet, cold, and dreary — weather I was well familiar with, being from Chicago, and I found it almost comforting. Despite the dour weather, life was well and alive around me. Young couples, around my age, laughed and chattered as they strolled past me, hand in hand. Groups of friends reveled in the streets, on their way to get another drink, or to crash for the night at someone’s place. Restaurants, bars, and pubs were busy at this time of the night, the soft glow of their windows inviting all those out in the cold into their warm domain. I walked past all of them, all the people, the places. Except for one.

Through the soft drone of the rain and the distant laughs and shouts, a haunting melody drifted, a melancholy sound — a saxophone. Surprised that anyone would be playing in this weather, I followed the music and arrived on a corner, where an old man was sitting on a small ledge, a case open at his feet, playing for an empty audience; no one seemed to notice him, and his case was devoid of any donations.

The old man looked up at me, and without pausing nodded toward one of two chairs next to him. Hesitantly, I dropped a 20-pound note, the last of my cash, into his case before sitting down next to him. No words were exchanged. The old man closed his eyes and went on playing his saxophone, as if I wasn’t next to him… as if everything that mattered in the world was himself, in that moment, playing his music.

As I sat, watching the pedestrians stroll by, the music began to have an odd effect on me. My eyes flickered and began to dim; my senses dragged away from me, and I seemed to slip into a state of conscious unconsciousness. All that was unclear began to come into view: the rain, which had only been a muddling veil over my eyes just moments before, was now

intriguingly clear; I could see every individual drop, falling in even lines around me. The steam from my breath looked almost solid, more than just a cloud; the haze around the street lamps and traffic lights became bright halos, while what was in their center, the lights themselves, remained cloudy and unfocused. Only the pedestrians stayed somewhat the same, but their faces were oddly blurred, features muddled and smeared, and they too seemed to be moving in slow motion — everything was moving in slow motion. Only the music marched on to its own tempo.

Voices, seemingly emanating from their bodies, reached my ears — disjointed rambling, sobbing, low muttering, and fearful wails — the sounds of regret, of pain, of a loss of direction; sounds akin to my own emotions, laying alone and despondent in my apartment. The music blended in with those voices. The saxophone seemed to draw them out, those painful emotions for the world to hear, breathing life into the realm I now resided in, that dreamlike ether of clairvoyance. It made the voices more clear, but not to the point where they were audible.

I was confused, of course, but calm. I had not felt so calm since the day I arrived in London, and it was as if the turbulence of the jazz surrounding me calmed the storm of emotions within me. I decided to focus on one particular pedestrian, an older man of about 60, wearing an old business suit. A wave of abandon and fatigue washed over me; I was feeling the man’s emotions. I saw his whole life flash before my eyes — born and raised in London, he had gotten a job early out of university like me, and had, well, wasted away, for lack of a better term. Never advanced in his career, never started a family, never made friends among his coworkers; he had stagnated his whole life, and the pain of regret and a bleak future raked his mind, and now mine as well.

I turned to another pedestrian. He was a young man, no older than 30, clutching his chest and weeping bitterly as he walked in this spectral world. This time, rather than a lifetime, I saw only one memory. He stood outside a cafe, watching as the girl he had loved since their childhood friendship, and was supposed to propose to months ago (he never worked up the courage), walked out arm in arm with another man. Forced to endure a short conversation with the couple, he rushed off, cursing himself for his own cowardice and hesitance, and walked the streets of London as a broken man. I felt his pain, his anguish, his regret, and I understood him as no one else could. I understood everyone in this hellish parade, this procession of destitution and tortured souls.

As I jumped from person to person, those torturous memories keeping me from dwelling on anyone for too long, more and more feelings of pain, of guilt, of regret, of self hatred, wracked my mind. A young woman had watched her friend jump to her death, lacking the initiative to tell her her mother’s death wasn’t her fault, that the fire in the house had been an electrical failure and not the stove she left on overnight. A middle aged man, straight backed but with an unusual set of gray hairs, walked listlessly after failing to convince himself to apply to a higher position several months ago, only to have his best friend turn on him and take it away — now, he had been laid off, and had nowhere to go. Person after person trailed one after another, in an almost endless train. I sat there for eternity, my stamina and sanity slowly wearing away as wave after wave of pain and suffering pulled me under. As I sank deeper and deeper, the music swam in circles around me, like a great serpent watching its prey struggle until the end. It no longer sounded melancholy; it was sinister, unforgiving, and just — it would force me to endure this ghastly orchestra of voices, all alone in this merciless hell.

After an unbearable amount of time, the procession came to an end, with one last person, who stopped and turned towards me. This pedestrian was different. He was almost purely haze, made up of a cloudy substance, almost like a ghost, and his face was clear, though colorless. With a jolt… I realized it was me. Older, certainly, but me.

No memory or life story came to me. There was no need. It was me. Someone I knew, someone I could understand more than anything in the world, yet someone so foreign and

incomprehensible to me that no vision, no revelation, no level of spiritual connection could ever allow me to truly accept. I knew how I had been languishing in my life, and I saw that if this continued, I would join the rest of them in that ghastly procession. I turned away, unable to look at myself much longer.

In doing so, I noticed that there was in fact one last member of the procession, trailing behind the rest. He was a man of about 35, wearing a dark brown blazer over a striped white dress shirt and red tie, with a well combed head of brown hair, and a gentle, kind smile. I felt no connection to him, and no spiritual or emotional vision came over me; if I hadn’t looked to the side, I wouldn’t have ever noticed him. He was simply just there, taking his time, without a care in the world.

He turned and walked towards me, crossing the distance leisurely in several steps. Pausing, he pulled out his wallet, and dropped a 20-pound note in the saxophonist’s case. “Mind if I sit?”

That was the first time someone had really spoken to me in this odd world. “Go ahead,” I replied, surprised that I could speak. He took his place in the other empty chair.

We sat there in silence for some time, gazing at the empty street in front of us. “You saw them, didn’t you? And you saw yourself among them.”

“Yes…” I said, my voice trailing off.

“People are like that,” the man said, sighing. “We all tend to turn away from what we should face.” We sat there in silence for another moment; then he smiled, and patted my shoulder, before standing up and walking off, following the procession that had since faded out of sight, leaving just me and the saxophonist behind, still playing that music which had since returned to its melancholy, cheerless tone, and I sat there, listening… as if everything that mattered in the world was myself, and the music, in that moment.

My ghost stood there, staring at me, as I watched it out of the corner of my eye. It seemed to be waiting for something. And I knew what it wanted. I stood up, turned and looked myself straight in the face. Though my ghost’s features were still blurred, I could almost make out a faint smile.

I blinked. Everything was gone. What was clear became unclear, what was unclear became clear again. I felt like I had just woken from a long, deep sleep; I felt groggy, my lips dry, my hands clammy and my legs weak. How long had it been? No time had elapsed from when I sat down to then. The street was once again filled with people, moving in real time now, and there were no more visions, no more haze surrounding them; no more ghosts.

The man was gone. The musician was gone, with his saxophone and his case — as if he had never been there in the first place. Only two twenty dollar bills, the man’s and mine, lay on the ground. I picked them up.

The rain was falling in earnest now. Walking back to my apartment, I briefly thought back on that experience. Was it a hallucination? I couldn’t tell. It was too much, too complicated and taxing to ponder. I would think over it tomorrow.