The Dearborns Down the Street

Renee Ge | Art by Alice Lu

Sometimes Mrs. Dearborn would fantasize about killing her husband. Usually after dark, never when he was awake. She would lay on her aching back and stare at the back of his thinning head for hours, listening to his bed-shaking snores and thinking all about the different ways she could do it. She could reach over and plunge her palm down on his soft windpipe, feel the way it pushed back and then gave. Smother him in his sleep with a pillow. There were knives in the kitchen drawer. They lived in a two-story house and the stairs were steep.

It wouldn’t even be difficult. Mrs. Dearborn thought of when they were both young, sleepy-eyed and stupid, holding hands in a pool of soft yellow light from a street lamp. There had been so much time. There had been so many dreams. It had all been so simple. “A house,” Mr. Dearborn had said. “A job. A nice neighborhood for the kids. Hell, everyone’s getting married, why not us?”

Now there was a house, Mr. Dearborn’s house. There was a job, Mr. Dearborn’s job. There was a nice neighborhood, all reds and whites and blues. No kids yet—Mr. Dearborn brought that up often. Then there were the things Mr. Dearborn hadn’t promised, but which still came true for her anyway: hours of thankless work and a peculiar listless feeling, the skin around her arms and face numb and dry enough to be part of the wallpaper. Her limbs felt almost detached from her body, and when she complained of headaches Mr. Dearborn made her lie down. Mrs. Dearborn did not know if the cause was age or Mr. Dearborn. Or both. Did Mr. Dearborn age her?

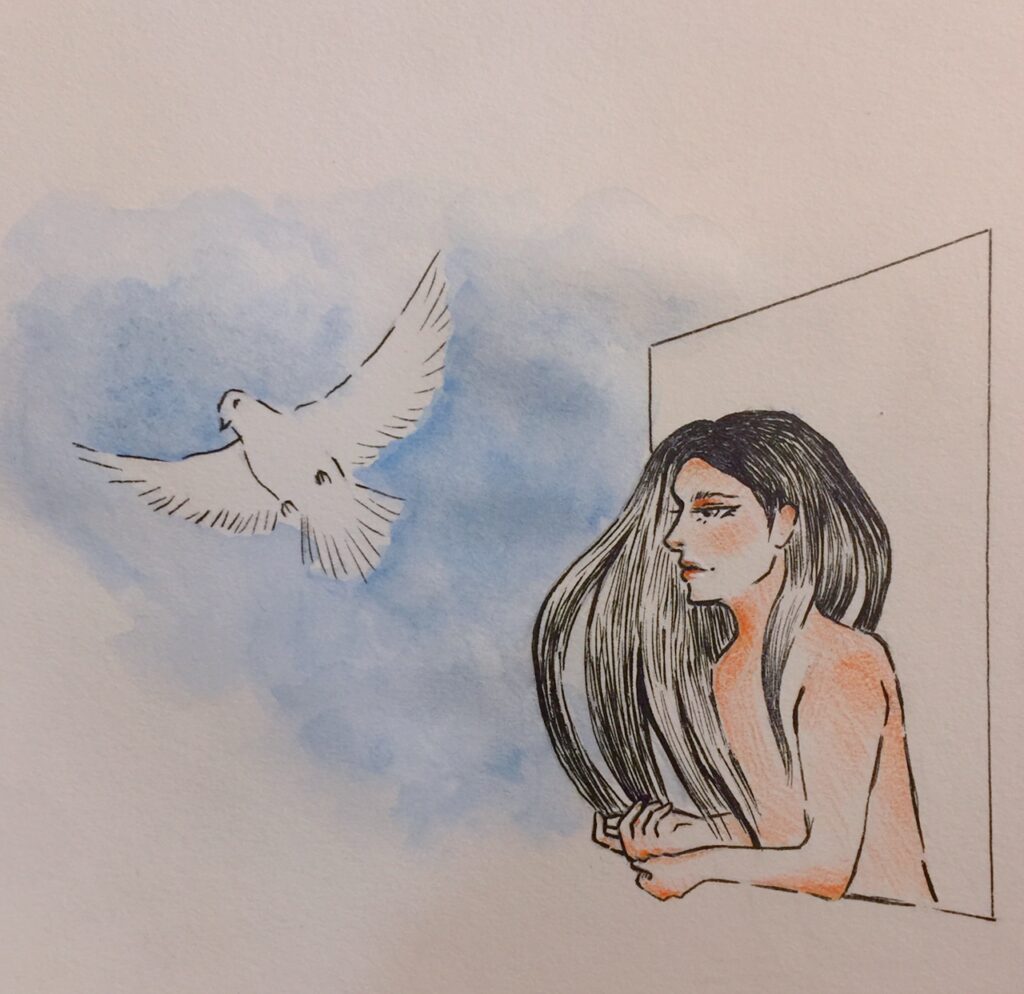

With some fascination, Mrs. Dearborn rolled over and concentrated on a dim point in the ceiling. What would her life have been like, if Mrs. Dearborn had never met Mr. Dearborn? She would have chosen New York or Paris, somewhere fast and loud and ready. She would go out simply for the pleasure of it, to museums and to gardens, where she could afford to look upon beautiful things and imagine she was one of them. She could be young forever. She wouldn’t have even been called Mrs. Dearborn.

What would her life be like now, if Mr. Dearborn suddenly disappeared?

Mrs. Dearborn got up. She did not dare turn on the hallway light. She clung to the railing and for the longest time, stopped on the widest step where the stairs began to curve, staring at the blackness which began to wrap around her and seep into her very bones. Slowly, she put one foot in front of the other.

There was no way the police would let her get away with it. She opened the drawer and picked up a knife. For some reason, she couldn’t suppress the sound of her footstops on the way up the stairs. Each thump matched the march of her heartbeat—steady, steady. Steady. A man dead, bed sheets wet with blood, wife gone in the night? Obvious. So obvious. She’d be in a real cell within a day. So why couldn’t she stop? Her limbs felt listless and detached again, wooden arms and legs manipulated by strings that fed into the darkness above.

She neared the bed. There lay Mr. Dearborn with his arms outstretched, as if waiting for a loving embrace. The pale light from outside bled through the curtains and traced curves and divots on his body with an artist’s hand. A portrait in monochrome. She turned to glowing curtains and felt as insubstantial and sickly as a ghost. Mrs. Dearborn was sorry. Mr. Dearborn’s life was equally unsatisfying. Being stuck somewhere between the cogs of the corporate world, performing the same job five days out of seven, and spending the other two in front of the television all conspired to leave him helpless in the throes of a vicious mid-life crisis. Somehow, somewhere, without either of them noticing, Mr. and Mrs. Dearborn had settled.

She—they could not live one more day like this. They simply could not. The knife in Mrs. Dearborn’s hands shook.

Someone behind her cleared his throat.

—

“Did you hear about what happened with the Dearborns?”

“Terrible, terrible. I can’t believe they’d do that, they seemed so nice. Why would anyone do that?”

“Who knows? Everybody’s crazy these days. I always thought it odd that they had no kids—something to do with that?”

“No, no, the husband told me, Mr…something…what’s his name? Oh, my God, what’s his name?”

“Doesn’t matter, what’d he tell you?”

“No, no, no. Oh, my god. What were their names?”