Ruby

Hannah Chung | Art by Maya Swaminathan

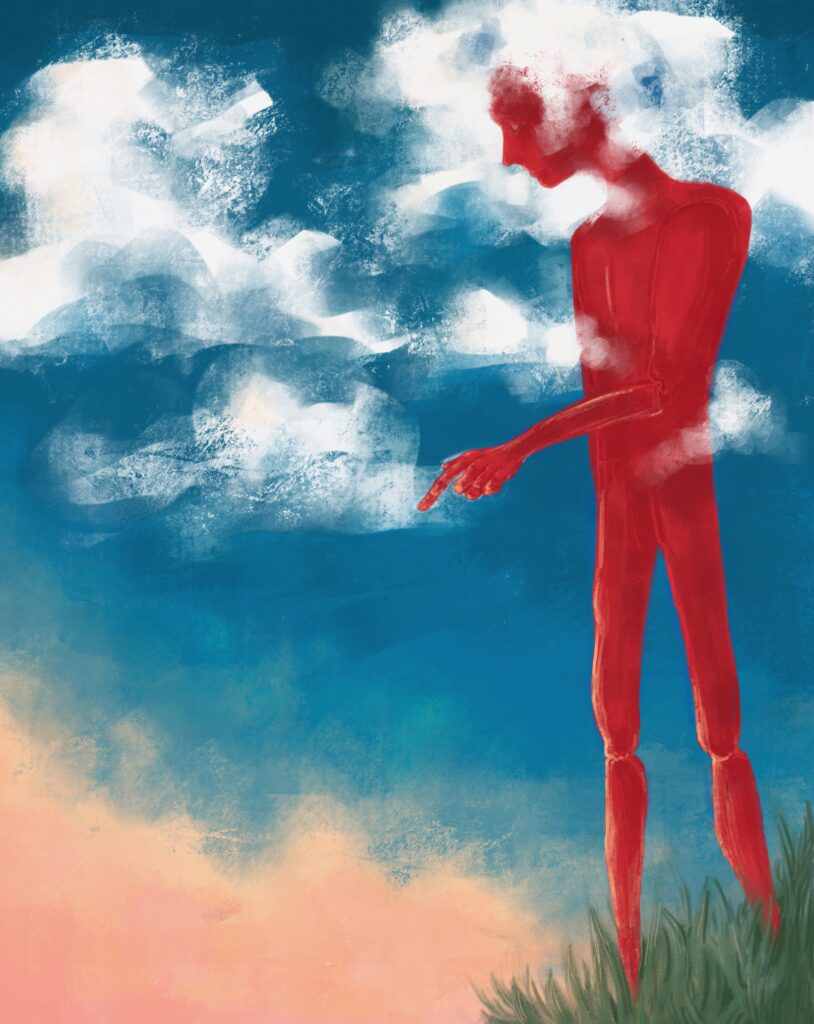

The roof is flat, which is perfect according to Ruby. It is sesame-seed-speckled with silica sand, and today is a very very still day, which is perfect according to Ruby. The air is hot and wet and low. Ruby is spindly and all edges and twelve feet above the ground.

She sniffs. There are clouds in the distance, impossible clouds. White and billowy like a Renaissance woman. Ruby thinks God must have whipped them into stiff egg peaks, scooped them up in his bare hand and molded them against the arid skyline.

Something about the grass is also impossible. It is long and green and willowy. It runs by the gravestones in the long pillowed mounds to the left of Ruby’s flat-roofed house. It climbs into the corpse beds, winds around one’s ankles. Is it immoral to say you are seduced by the dead? Ruby doesn’t know this; Ruby doesn’t think about this.

Instead, Ruby thinks about how she often rode her bicycle on still, still days. Faster and faster, making a bike and cul-de-sac acute angle until her body extended into a fleshy hypotenuse. Until her flat squat house and the lumpy green resting places and the house with two small dogs all blurred together into one. The funny thing was that when it all looked the same, everything became perfectly still — mossy-toothed gravestone becomes garden cat; dented Prius is mother calling for dinner, the smell of neighbor’s barbecue wafting is the haunted hunted dove cry. Streetlight yellow-blue twilight proud and quiet and tall, becomes grass, becomes yellow child’s chalk.

It is July and the sounds of wind and engines swell and ebb. Wait three seconds at each four-way. There are two on the way to Ruby’s house. In the distance, a screen door pushed by the wind creaks strangely, slowly. Before Ruby makes contact with the asphalt, she tilts her head once more; looks at it still still still.