the painter

Crystal Zhu | Art by Annie Yao

This is my first coherent memory.

It started when the jeep was at a particularly bumpy part of the road. Tires chewed the dirt slowly as the driver navigated the mountain paths. I looked out the window, the straight arms of trees racing past. I can’t tell how old I was. Five, I think. We were driving. We might have driven for five minutes, or for two hours, but the destination arrived as if within seconds.

It was a house at the end of a rough pebble path, it couldn’t have been much bigger than a cottage, maybe, but it did have many rooms. So it couldn’t have been that small. Anyways, I’m getting ahead of myself. The rooms don’t come until later. My dad got out of the car and took my bag out of the trunk. He smiled at me.

I shouldered my own bag, which was a light lavender that I really liked. In there was a book my dad told me to “occupy yourself with while I talk business.” The driver came with us. He took our suitcases under each arm while my dad strode up to the rickety house. I followed him closely, because despite the sun, the forest felt whispery behind my back.

My dad knocked on the imposing door. My dad wasn’t one of those “knock before you enter” kind of guys. So, this surprised me. Then when the door opened, my dad gave a hat tip, and said “Greetings, sir.” He wasn’t one of those hat tipping, respect giving guys either. This surprised me also.

I peeked around my dad to see whoever it was that inspired such change. At first, I thought it was a turtle. His cheeks were a mass of canyons, and when he smiled, his face split into two continents. A wisp of a goatee hung from his chin like a dying waterfall.

They exchanged some words. The next second, we’re in the house. It’s sleeker than I imagined, neat to the point of Spartan. The central room had a simple settee, a coffee table and a pot of lilies. There were paintings on the walls, lots of them. I tried to talk to the Turtle Man, but my dad said, “Find her a room.”

Turtle Man took me from my dad and led me into a guest room. It’s small and only has a single white bed tucked in a corner.

“Do you have a lot of rooms? I saw a lot of doors.” I asked Turtle Man. He said, “Yes,” and left, but didn’t completely shut the door. I remember feeling grateful for this, because I never liked closed doors. I heard the sound of pouring tea, then Turtle Man came in again, and handed me not tea, but a glass of milk. He left a second time.

I read my book. I recall the room being a dreamy blue color, but it might have warped over time. Hours passed, I think. Talking was low voiced and constant. The sun slid down the window and I found the light switch. More time slipped past. I finished my book and waited. Finally, my dad came in. He had my suitcase and a tray.

“We’re staying for tonight,” My dad said, “I’ll be in the room beside yours.”

I wondered how many rooms there were. I imagined rooms like sunbeams, like labyrinths, like mossy dungeons. I ate a sandwich, which the tray contained. After my dad left, I unpacked my bag. That’s when Turtle Man knocked on the door.

“Come in,” I said, and Turtle Man walked in, put his hand out and said, “Do you want to see the other rooms?”

I said yes, and followed him out. Any older, and I wouldn’t have been so innocent as to follow an old man into his unfamiliar home. But I was at that age where I was willing to put trust in anybody.

The central room was lit by nothing but a single lantern on the coffee table, which was strange because I knew he had electricity.

“What’s your name?” I asked, and Turtle Man smiled.

“Tom,” he said.

Huh, Tom. A common name. Fitting or not, I couldn’t tell.

He had my hand firmly in his, and he took the lantern from the table. The first room we entered was identical to the one I stayed in, but its walls were covered with paintings. Paintings upon paintings upon paintings. There’s pine trees and sandy beaches and snowy mountains, and duplicates of all of them that had clearly been painted at different times. I could see the pattern of paint where the brush met the paper like undulating waves.

Turtle Man took me out of the room and into the next one, and it’s the same in my memory. The same paintings. Maybe I only remember the first room and the last room, I’m not sure. He showed me more rooms than I can count. In my memory, they are infinite, stretching away like mirrors reflected on each other. But at the last one, he paused outside the door and put a finger to his lips. I mirrored his movement and he nodded.

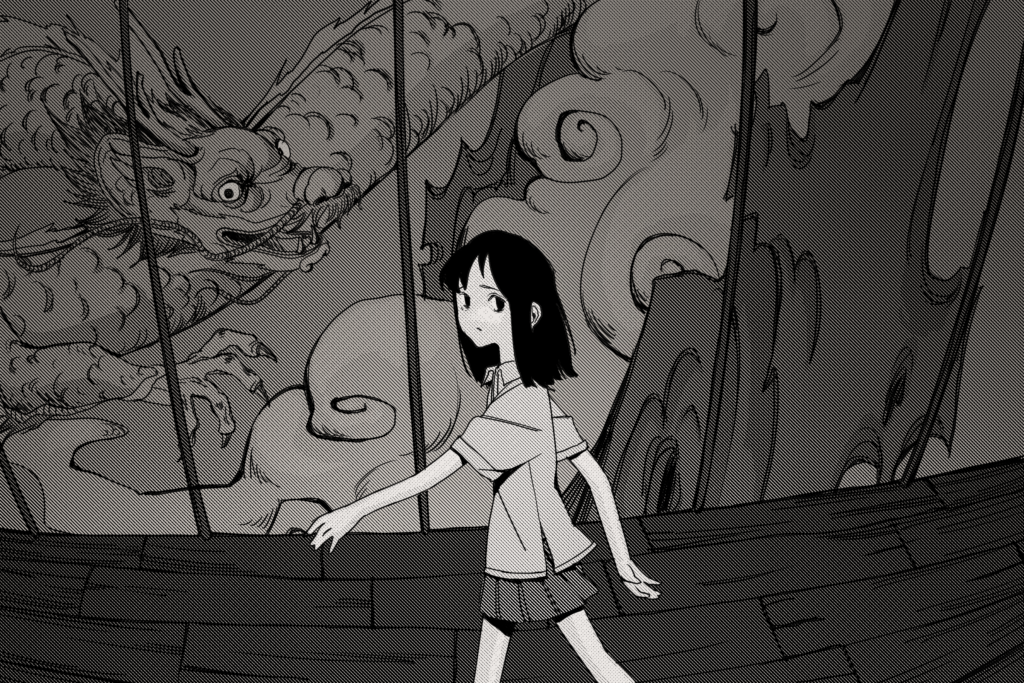

The quiet was supreme when we entered, and I realized there were no paintings at all on the walls, but there was actually one painting. A big one that spanned the entire room, a single unending strip of papyrus. This one had only ink and paper, a sprawling range of mountains and twisting trees, and a river and a house. This house. It was a dragon lunging across space, a galaxy of nebulas.

I blinked and breathed because that was the only thing I could do. Turtle Man wasn’t smiling. His face was like a pool that no one has disturbed in a thousand years.

“Do you know what color this is?” he asked.

There is no color, I wanted to say. I shook my head instead.

He looked down and the lantern’s light flied across his creviced face and he said, “It’s all the colors of the universe.”

I don’t remember what happened after that. I think I went to sleep then, because the next thing was eating breakfast on his settee as the morning sun played.

“I haven’t made a painting in a while.” Tom said, sipping his tea, “Inspiration, you know, hard to come by.”

“Yes, but you could make a sizable sum. I’m not the only one looking for your paintings.” My dad replied.

“I told you, I’m only selling one painting. Maybe the city will be better for my soul.”

“If you could’ve sold that painting, why did you stay here for so long?”

My memory doesn’t contain his exact reply. I think it involved something about ink running dry when it was time, or was it to find his own ink somewhere else?

When we left, we had his floor-to-ceiling tapestry in our car trunk, packed with awfully great care. Money was transferred.

“Don’t damage the antique,” my dad said. I wanted to ask why it was an antique when it was so clearly all around us, in the mountains, in the trees.

Turtle Man just disappeared after that. Like he wasn’t there at all, like he was an actual turtle and the house was his shell.

We drove away with the painting in our trunk. My dad hummed to a song.

A while down the mountain, a giant truck passed us. I remember so clearly the white of its vast hide against the emerald trees. I think now that it was a moving truck. Must have been for Tom.

I asked my dad why Turtle Man gave us his painting.

I don’t remember his exact words, but it was something like folks needing money, and Tom was struggling a bit and wasn’t the painting so gorgeous.

Not so gorgeous rolled up in our trunk. I looked out the window.

The truck, I thought, it was so out of place.